By Janet Dunn in association with

Despite the many conveniences and advantages of modern life, wellbeing and contentment continue to evade many of us. The cure may be in an architectural concept that sounds new but is as old as the hills. Take a dose of biophilia and read how your home’s design can help you live a healthier, less stressful life.

THE TALE OF A TIGER

Tony the Siberian-Bengal tiger was an attraction at a truck stop in Louisiana, USA until recently, when his life – lived out in a cage outside the petrol station – was cut short due to illness. The tiger spent most of his 17 years in the fume-filled artificial habitat, but had his owner known more about the links between an animal’s surroundings and its health and happiness, Tony’s story may have ended differently.

Is there a lesson humans can take from Tony’s fate? Deprived of sensory stimuli, social bonds and connection with nature in our homes and workplaces, we may be heading down the same path. Biophilic design is being advanced as the next important focus in architecture and as a remedy, partly, for the plethora of modern-day conditions linked to fatigue and stress.

WHAT IS BIOPHILIC DESIGN?

Biophilia literally translates as ‘love of life’. In the 1980s, American biologist E. O. Wilson proposed that evolution has soft-wired us to prefer natural settings over built environments. In Wilson’s words, we have “an innate and genetically determined affinity … with the natural world”. Exponents of biophilic design are attempting to address this instinct architecturally.

Photo by Brickworks Building Products

Essential to biophilic theory is the idea that buildings aid our physical and mental health only when they are designed holistically. Rather than isolated elements – for example, simply putting plants in a building – benefits occur when diverse and complementary factors reinforce our experiences of nature. Wilson’s colleague Dr Steven Kellert named plants and natural lighting, and indirect influences through shapes, forms and materials that originate in the natural world, as some of the attributes of this kind of design.

IS IT JUST ANOTHER NAME FOR GREEN ARCHITECTURE?

Green building principles emphasise responsibility to the environment and efficient use of sustainable resources. Although biophilic design embraces these aims, its focus is more on the wellbeing of those who use the spaces.

The merging of planet-based with human-based philosophies is causing a stir in architectural circles. Brian Donovan of BVN Donovan Hill commented that “architecture will never be the same again”.

WHAT’S NEW ABOUT IT?

Biophilic design is a rediscovery of an ancient practice, not a new idea. For aeons, architects have recognised the place of humans in a wider ecosystem and integrated natural elements into built forms. Athens’ Parthenon, Rome’s Pantheon, and the ancient Vietnamese city of Hoi An are examples of biophilic design at work, although the label wasn’t attached until the 1980s.

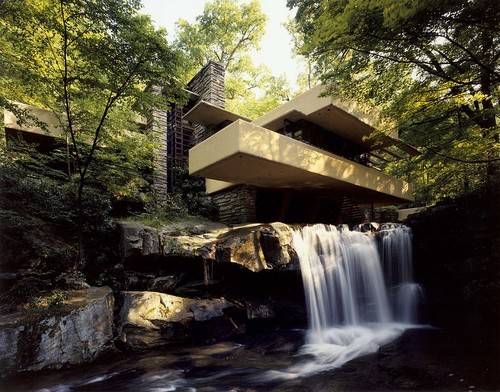

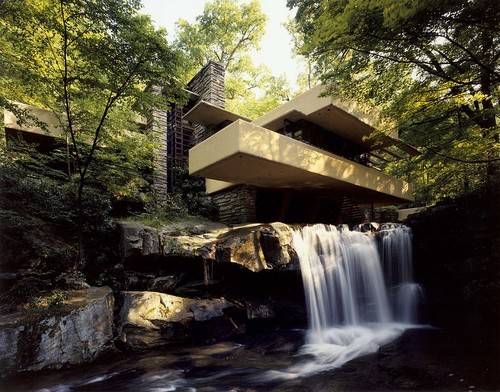

By Fallingwater Mill Run

Frank Lloyd Wright was a more recent exponent of biophilia. “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you,” he advised, and many of his buildings bear this out. Notably, his groundbreaking Fallingwater (pictured above) is so integrated with nature as to be inseparable.

WHY ARE WE TALKING ABOUT IT NOW?

Today, the concept of biophilia is supported by a more scientific understanding of the psychology behind building-based wellness. Exponents of biophilic design believe the large proportion of time we spend in built environments may contribute significantly to feelings of isolation, tension and lethargy.

Today, there is growing interest in designing restorative, productive and appealing buildings with sustained opportunities to engage with natural systems. Workplaces, medical and aged care facilities and, vitally, our homes are set to benefit hugely from this trend.

WHAT ARE THE ELEMENTS OF BIOPHILIC DESIGN?

- Natural light from windows, skylights, clerestory openings; full-spectrum artificial light sources that complement daylight; dynamic light of varying intensity via facades, shades, shutters and apertures.

- Exterior views. A distant view past a close view gives perspective and a sense of connection to a wider ecosystem.

- Water sources such as fountains, ponds and water features, that can be seen, heard and touched.

- Rich sensory stimuli that reference nature; scented plants, plants that change colour seasonally, plants positioned to move in breezeways, open flames, tactile materials.

- Minimally processed materials that reflect the local ecology; natural fibres such as leather, stone, timber and handmade objects.